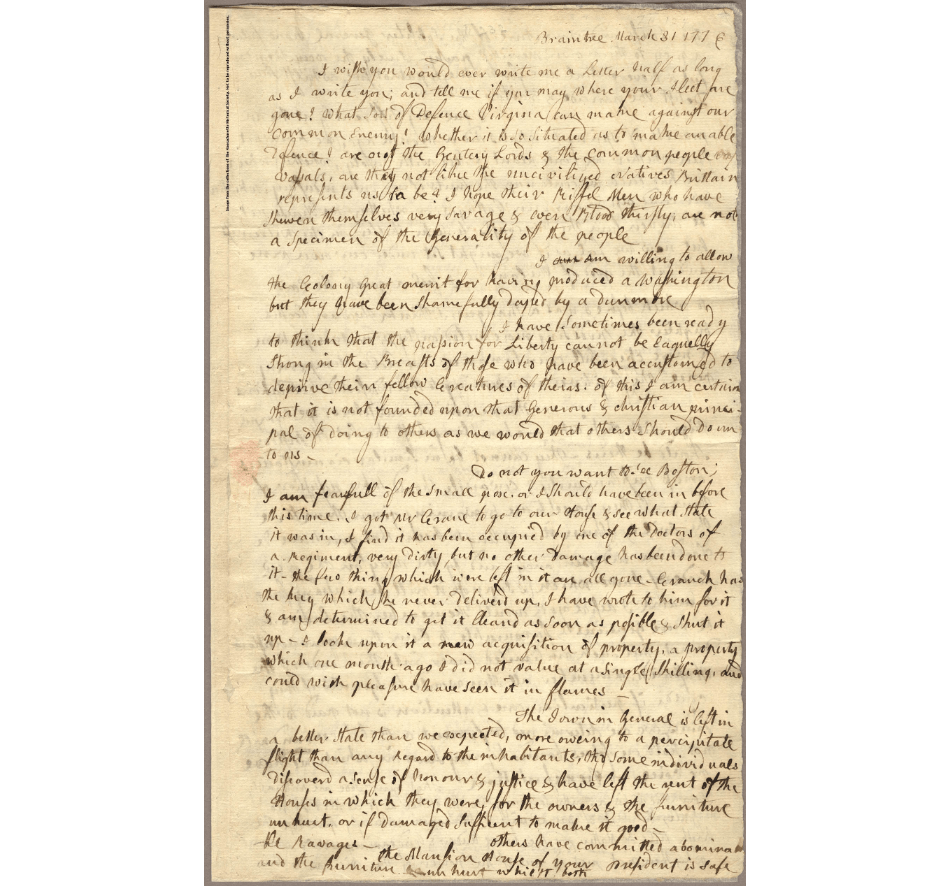

(Massachusetts Historical Society, c.1800)

With the rise of Women’s history and Social history in the 1960’s, history since then has often reflected the interests of activist agendas. One such document that presented present-day activists with much resonance is Abigail Adams’ series of letters to John Adams, more commonly referred to as ‘The Adams’ Letters.’

On 31st March 1776, Abigail Adams wrote a letter to her husband, John Adams, in an attempt to persuade John of the need for women’s protection by law. As John was making his way to draft what would later be called the U.S. Declaration of Independence, Abigail’s words to one of the nation’s so-called ‘Founding Fathers’ bares particular weight on how we view the constitution in relation to the cause of women’s rights in today’s context, not to mention her own.

Abigail’s words echo an ongoing political discourse of her time: a discourse on individual liberty and autonomy with which her audience, John, was directly involved. Although her logic was too far from that of the mainstream to be endorsed by John, Abigail makes several significant points that extend the revolutionary cause to women, drawing upon multiple intellectual traditions that strengthen the authority of her non traditional reasoning. Primarily, metaphorical allusions to two political concepts allow Abigail to link the cause of women to that of the founding fathers: independence and slavery.

Abigail opens her letter with an appeal to the revolutionary cause of independence. A direct response to the news that a declaration of independence was soon to come, Abigail’s letter unfolds with a sympathetic gesture (that she longs ‘to hear that you have declared an independency) towards a cause for which John is striving. In doing so, Abigail succinctly casts metaphors that associate the image of the patriarch with an absolute monarch.

For instance, Abigail predicates that ‘all men would be tyrants if they could’, advising that John should not endow ‘unlimited power’ to men. Using metaphorical language that equates the state of women to that of the American colonies in relation to the monarch, Abigail makes a subtle yet compelling case to extend the revolutionary cause to women. Hence, Abigail implicitly suggests that it would be contradictory for John to support the revolutionary cause while not addressing women’s legal protection.

Abigail Adams, “Letter to John Adams” (31 March 1776)

(Massachusetts Historical Society, 1776)

“I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone?

What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence?

Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be?

I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people.

I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.

I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs.

Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us. . . .

I long to hear that you have declared an independancy— and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors.

Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands.

Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could.

If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend.

Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex.

Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in immitation of the Supreem Being make use of that power only for our happiness.”

The Language of Women’s Protection

Another concept that Abigail invokes to argue her case is slavery. Repeatedly utilising metaphorical language, this time between the patriarch and the enslaver, Abigail portrays harsh husbands as ‘Masters’ and those sympathetic to the cause as ‘friends’. This linkage between the state of slaves and women is cleverly designed to touch upon ongoing political tensions among Abigail’s contemporaries, including John’s own views on slavery and the conflict of interests among the Northern and Southern colonies.

During the creation of the Declaration, the founding fathers avoided directly mentioning the issue of slavery for fear of alienating the slave owners in the Southern colonies. John Adams, for one, was opposed to the use of slaves in favour of freemen labourers. Abigail, knowing John’s position on slavery, also exploits this fact to argue that the revolutionary cause should be extended to women. Abigail then expounds on how women would be determined to ‘foment a rebellion’ under laws that do not cater to the unequal state of women.

Appealing to the same concerns that confronted her husband regarding the possibility of factions over the issue of slavery, Abigail uses John’s logic against himself to persuade him that women’s legal protection was, in fact, ‘rational’ under his logic. For Abigail, it is essential to include a clause that reflects women’s interest in the new code of laws, as much as it is essential for John to concede to the interests of the Southern slave owners to prevent a rebellion.

Radical or Moderate: Was Abigail Adams “Feminist”?

It is worth discussing the extent to which Abigail is advocating for a sort of “women’s rebellion” when she mentions its possibility. As radical as Abigail’s suggestion for women’s legal protection was, a manifesto for a social movement against patriarchal governance in Abigail’s time would be unthinkable. However, the private character of the document, designed for the readership of a single John Adams, demonstrates that Abigail’s purpose could not have been to deliver a public manifesto. Without additional sources to clarify her motives, Abigail’s true intentions about a women’s rebellion remain obscure.

Nevertheless, it is certain that, as far as this document is concerned, her intentions were never to foment thousands but to persuade a single audience, her husband. Abigail’s true purpose of mentioning a women’s rebellion here is to argue that women be recognised ‘voice, or Representation’ in the new code of laws.

Abigail’s argument for legal recognition takes on a religious language towards her proposed solution. Towards her final remarks, Abigail asks John to think of women as beings that are to be protected by men under ‘providence’ and to use the power of men for women’s happiness, as does God, or ‘the Supreem Being’. Abigail does not concern her solution with voting rights nor equality between the sexes; she accepts that women are subjects to be protected by men and argues for this ‘protection’ to be legally stipulated in the new nation. According to Abigail, laws were to protect women as subjects of God from unrestricted masculine power. Hence, Abigail concludes that men, as the ruling sex, must legally recognise women’s need for protection.

Abigail’s letter has attained much social and scholarly attention in posterity, especially by activists who read Abigail as a feminist thinker. However, from her Letter to John Adams, we see that Abigail herself did not intend to advocate for a change in inequality through social action. Even the very nature of the document (a private letter) tells us that Abigail could not have foreseen her writing gaining the social significance it did over the centuries. To avoid imposing present values on past subjects, we must treat ideas as articulations against their respective historical contexts, not as disembodied beings independent from time and space.

In this sense, Abigail is addressing the cause for women in a distinctly different way from the feminist thinkers of the twentieth century. In the present, her resolution for the legal recognition of women as subjects to be ‘protected’ is no longer radical nor deemed necessarily appropriate. To meaningfully place Abigail’s ideas into our present debates would require a critical interrogation into the late-eighteenth-century political environment, not a unilateral ‘application’ of her words into our own.