Is the ‘environment’ natural?

Before we begin, what even is the “environment”? We often think of the environment as synonymous with the natural world of animals, plants, and landscapes, where human civilisation hasn’t had its reach yet. A quick search on Google image reveals pictures of green, sublime images of the natural landscape. The dictionary definition of the environment is “the circumstances, objects, or conditions by which one is surrounded.” But such definitions seem a little absurd. Though we colloquially consider forests, mountains, rivers, and the biomes that inhabit it as part of the ‘natural environment,’ the border between what is natural and what is not becomes less clear-cut when we come closer to our own spheres of life. For instance, the pet dogs, domesticated cats, the eggs in the grocery store, roadside trees in the middle of the city… these are all, by right, part of ‘nature,’ yet we rarely think of them as part of the environment compared to their wild counterparts.

There is, however, one consistency in all these vague definitions of the environment:

- that our different depictions of the ‘environment’ are all devoid of humans, and

- that the closer natural organisms are to humans, they are considered ‘social’ rather that ‘environmental’ (for instance, leaves on a forest are considered to be part of the environment, whereas the parsley on my pasta for lunch today is not)

Rather than having a stable definition in itself, we seem to think of the environment in terms of what it is not. In essence, we seem to think of the environment as anything not human.

In today’s blog post, I wish to complicate this dichotomy a bit further. Studying the history of ideas (or ‘intellectual history’ as academics call it) tells us that there is a history to every abstract category. By looking at how categories such as gender, race, class, or ethnicity have been constructed by the ideas that people attribute to them, we can see how the categories we use colloquially today are not natural but artificial and human-made.

But what about the ‘environment’? Some might consider it heretical to even question this categorisation. After all, the (natural) environment should be a pretty natural one, shouldn’t it? Even in the light of the current climate crisis and the wave of environmentalist movement following it, many would probably object to the act of trying to bring in any ‘human’ elements to the untouched, sublime environment. Still, since when did we start thinking of the environment as something separate from humans? Do we necessarily think about our surroundings the same way that people in medieval Europe did? Since when did we start distinguishing ourselves from our plant and animal counterparts to think of ourselves as part of a greater, super-human “society”? In other words, what is the history of the ‘environment’ as an idea?

Constructing the ‘Wilderness’ – The Case of North America

History reveals that there is nothing ‘natural’ about the environment. Our definition of the environment as something separate from human society is, as it turns out, an extremely Western one. Looking at the history of non-European lands, of non-White oppressed races and nations, we see that the environmental space was constructed with concretely political aims.

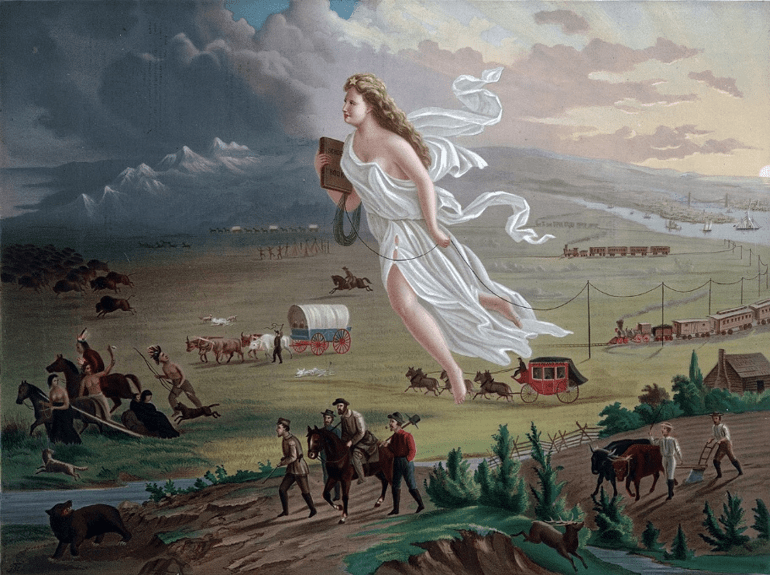

The history of U.S. expansion in North America is a representative example of one such environmental space was constructed. From the 19th century onwards, the ‘wilderness’ beyond the U.S. Western border was seen as a sublime land untouched by human civilisation. As religious ideals of ‘God within nature’ grew stronger in transcendentalist movements of the 19th century, the North American wilderness became a glorified project for U.S. expansionist politicians. At the heart of this conceptualisation was the idea of an environmental space of the American ‘wilderness’ – a land thought to be untouched, untainted, and thus had yet to be developed by U.S. civilisation.

The problem of ‘wilderness’ is that the lands west of the U.S. were not untouched at all. In reality, the Western part of North America was densely populated by sophisticated societies of non-white tribes and rural farmers. Still, conquering an untouched ‘wilderness’ was easier than acquiring control over a land densely populated by diverse local peoples. As the wilderness was thought to be separate from human society, people in the U.S. did not oblige U.S. expansionist politics regarding the area as a matter of politics. Thus, depicting the western lands as an untouched wilderness enabled a depoliticization of a process that was, in fact, highly political and oppressive.

Claiming an untouched ‘environment’ was easier than claiming a land densely populated by local non-white populations.

The history of ‘indigenous’ land appropriation shows how this ‘environment’ was not natural but in fact had very political repercussions (be mindful that the term ‘indigenous’ is an umbrella term that imposes a Western viewpoint that masks the variety of local tribal nations in the Americas). In 1871, the Indian Appropriations Act declared that ‘no Indian nation or tribe within the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation.’ The 1871 act mandated the forced relocation of these tribes to Indian reserves where they would be segregated and culturally ‘preserved’ from the influence of U.S. civilisation. In the solidification of U.S. nationhood, the existence of ‘savage’ tribal peoples in a ‘civilised’ nation like the U.S. was unacceptable. The frontier between the environmental ‘wilderness’ and society was actually one between diverse local non-whites and the U.S. empire.

Why we should think intersectionally when thinking about the environment

Therefore, environmental history is just about the ‘environment’ per se. The very definition of ‘environment’ (the surroundings in which an actor lives or operates) assumes that there is another subject that is central to its characterisation. Ignoring this component of environmental history by treating it as a discipline that only records facts about nature, biomes, and climates degrades the potential that history holds in an age such as ours. In essence, excluding humans from environmental history dehumanises and, consequently, depoliticises the discipline.

The current climate crisis is a distinctly human-made one and solving the crisis will require distinctly human approaches to the historical and political issues that complicate its solution. We cannot just wait for scientists to save the day. History has revealed that certain individuals or groups hold more responsibility than others in this crisis; ironically, those groups are also the ones that hold more power to bring about change for the better. Environmentalism and the struggle for environmental justice can only be sustainable when people of all races, ethnicities, genders, sexualities, classes, and nationalities have an equal voice in the solution. This is why we must think historically when thinking about the environment.