Time is running out. Temperatures have gotten hotter and sea levels higher. Scientists in the IPCC’s 6th Report have told us we have less than a decade to cross the 2°C point-of-no-return. Although we are keenly aware of ‘what’ we are supposed to battle, we seem to be completely lost on ‘how’ to bring about these changes that scientists remind us about. As we frown upon climate-change deniers while turning to science for objective solutions, we cannot help but ask: “Is there nothing we can do to help?” As non-specialists, are we meant to stand by and watch until the scientists come to save the day? In other words, what do history, politics, or ethics have to offer for the current climate crisis?

The history of environmentalism may offer an insight. From the early-twentieth century, conservationist movements started arguing against the devastating effects of human technology on nature. Thanks to this first wave of activists, the familiar narrative of human destruction of the natural environment became increasingly popular.

However, not all environmentalists were satisfied with this narrative. Aldo Leopold, a U.S. ecologist, was one of them. In his Land Ethic, Leopold argued that people were not thinking ‘ethically’ enough about the land.

For Leopold, ‘ethics’ is a cooperative mechanism that limits individual freedom for the sake of existence in a community. Simply put, if we slapped any random person we met, we would be exercising unlimited freedom. However, such disruptive acts are seen as intolerable to peaceful coexistence. To prevent this, we place a moral high ground on the act of ‘not slapping others.’ This enables any institutional penalties that may follow actions that cross this rule. Ethics is the mechanism behind this process that curtails our freedom to slap anyone to maintain our community.

Here, Leopold asks: “Do we ever restrict our freedom when taking from the land?” As humans, we are not only members of the social community but also the biotic community. However, there was no concept of ‘ethics’ when people imagined their relationship with nature, unlike that with humans. Particularly, Leopold was discontent with how people only thought of the land in economic terms: an exploitable resource, not a base of human life.

This ‘unethical’ way of thinking did not only result in environmental destruction. It also complicated the solution by shaping the language conservationists used to argue their case. As activists at the time argued only for the “economic” benefits of conservation, the non-profitable parts of nature (deserts, marshlands, etc.) were often disregarded, even though the “profitable” parts depended on these “non-profitable” parts for ecological regeneration.

Once we think of ourselves as members, not conquerors, of the ecological community, it only makes sense to limit our power to exploit the environment as its most powerful member. (Just as we wouldn’t punch someone weaker than us on the street for economic gains.) For Leopold, the land was where ethics ended and where economics started.

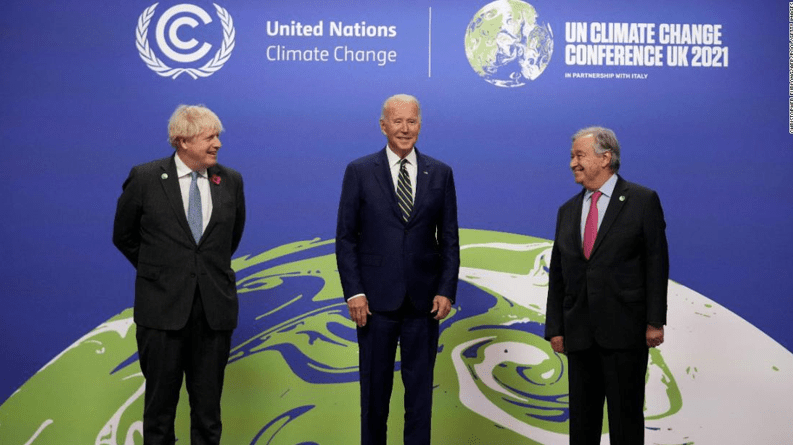

Then, is our perception of the current crisis any less problematic? Are we regarding the environment as we should? A look at the final pact of the Glasgow COP26 summit should tell us something about our current state.

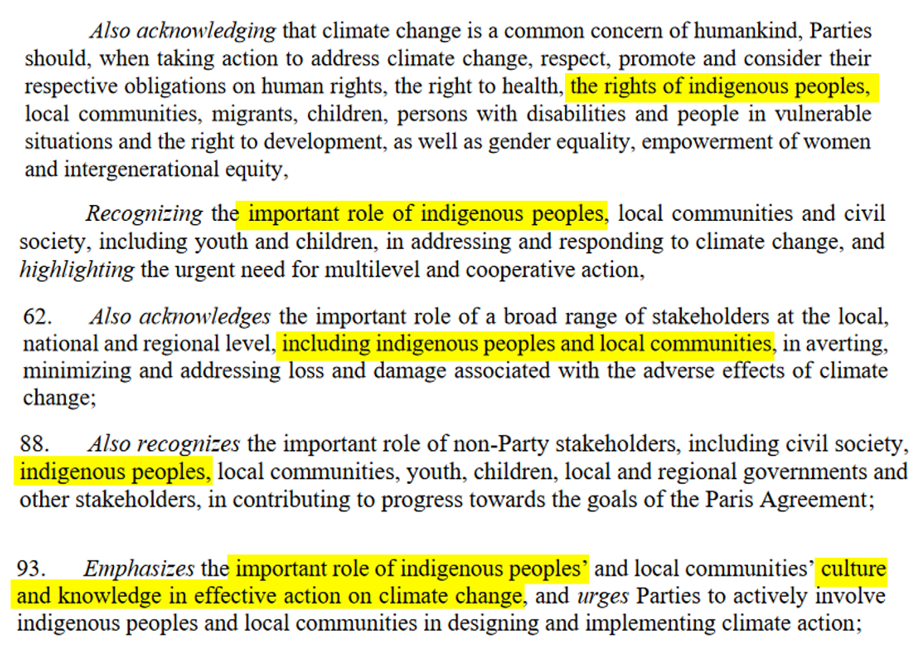

The COP26 summit addressed various issues, including the incorporation of indigenous people when consulting environmental issues. However, what is not mentioned is sometimes more important than what is. Nowhere do they mention who they mean by “indigenous peoples.” How they will consider the opinions of these people remains a mystery. Most absurdly, just outside of the gates of COP26 in Glasgow, a group of indigenous activists were protesting for representation. Ironically, COP26 was blocking out the exact people they promised to listen to.

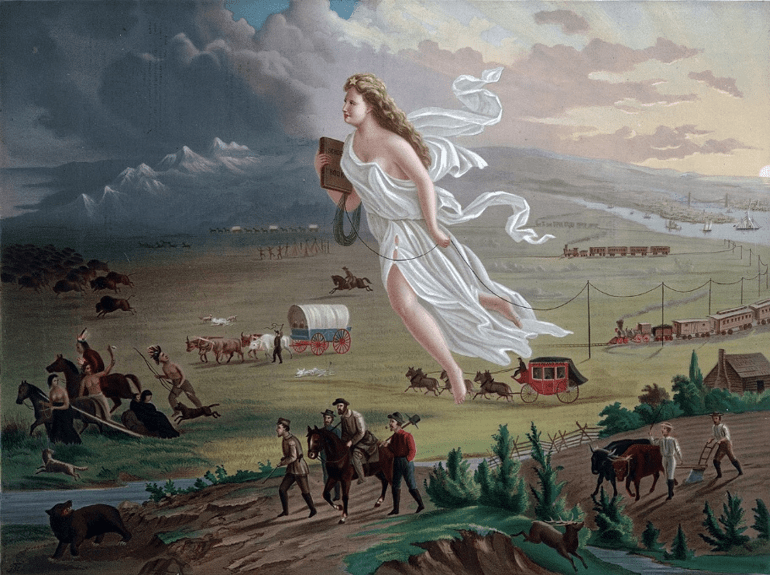

The dictionary definition of indigenous is to “originate naturally from a particular land.” Under this definition, no race is indigenous to America: we all have migrated from Africa at some point in history. However, only people present in America before Columbus are considered “indigenous.” (We wouldn’t call a white person born in New York an “indigenous New Yorker.”) This implies how “indigenous” is a term coined from a European viewpoint that swipes numerous tribal nations under the carpet.

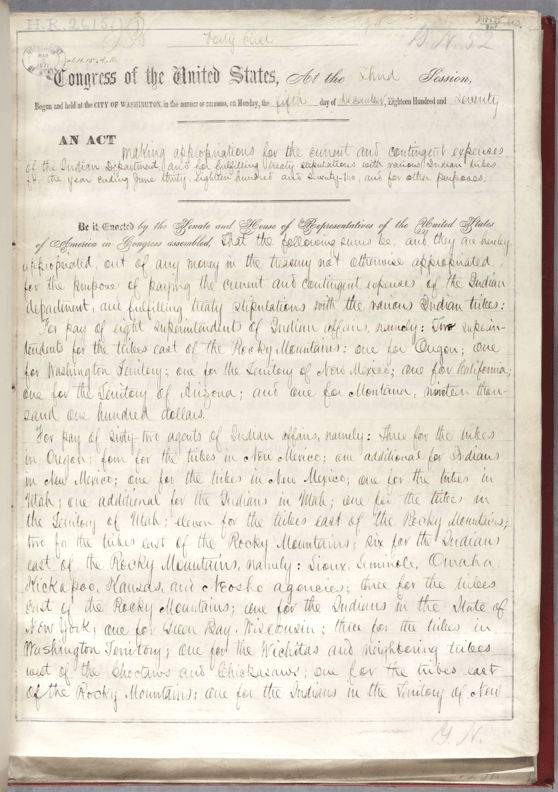

The biggest problem with this term is that, historically, “indigeneity” was used to oppress non-white people. In the nineteenth century, U.S. officials used the fact that these people maintained a lifestyle closer to nature to suggest that they were “backwards” and “primitive.” These racist assumptions were then used to appropriate their lands for U.S. benefit. Policies like the Indian Appropriations Act (1871) were justified on the basis that the “savages” of the tribal nations were not “civilised” enough to rationally use the land. The continuing tendency to view indigenous peoples as close to nature, yet not consider their voices with political weight implies a significant problem in resolving the climate crisis.

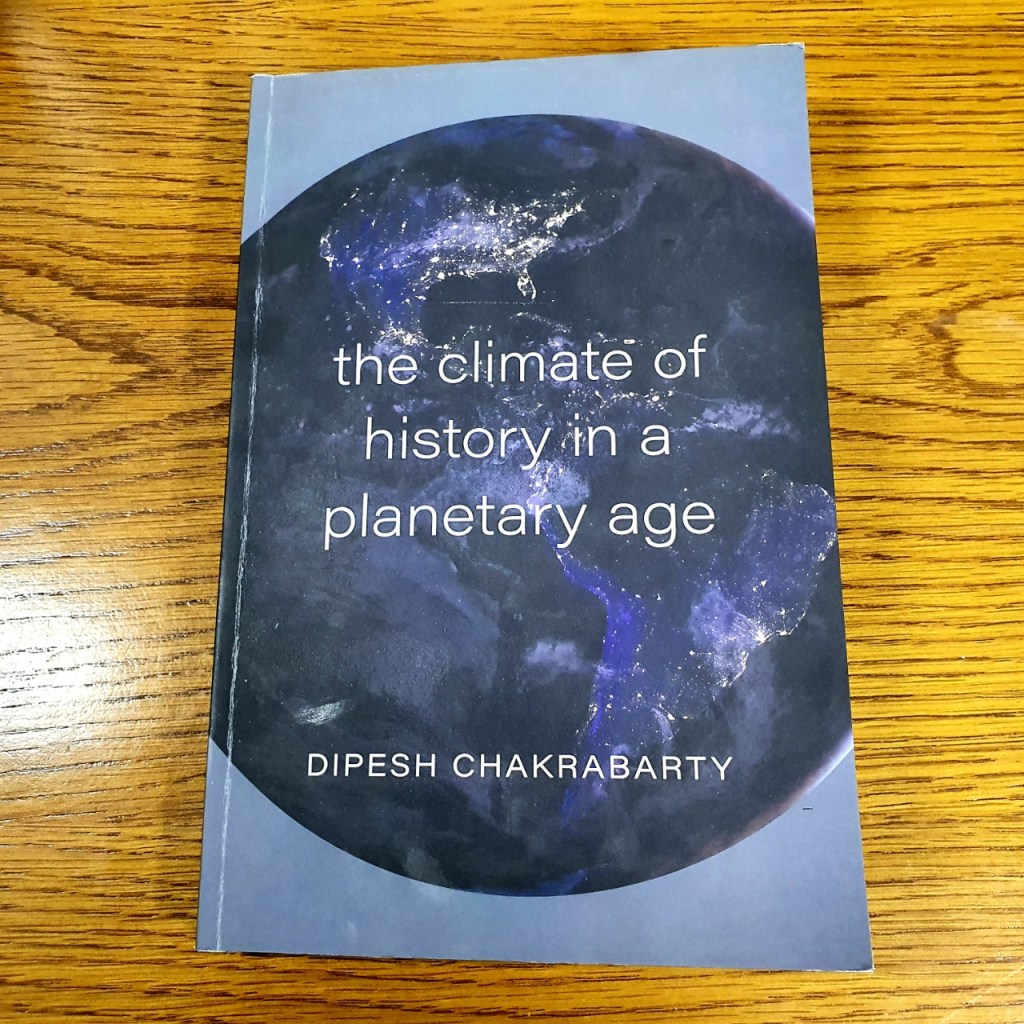

We must think more politically when speaking of the environment. The history of environmentalism shows us that climate justice cannot be achieved by fighting within the conventional concepts made to separate nature from human life. As the conservationists of Leopold’s era were not thinking ethically enough about nature, the Glasgow Climate Pact shows us that we ourselves are not thinking politically enough about the human frameworks that underline the natural, scientific aspects of climate change. The failure of COP26 to represent grassroots protesters proves that we cannot rely on “experts” and heads-of-states to do this rethinking for us.

In this, history can be of useful service. History has the power to denaturalise. By looking at the history of how ideas like ‘ethics,’ ‘indigenous,’ or ‘environment’ were constructed, we can challenge traditional concepts that people often tend to assume as given. As the problem of climate change is always structural than individual, it is not enough to address environmental issues without tackling the political agendas that complicate its solution. We must continue to think beyond the categories we have grown accustomed to for so long. Time is of the essence.