The ‘total,’ it seems, is more of a myth to the historian nowadays. Although many historians have attempted to brand their work to capture the ‘total’ in the names of world history, global history, macro history, l’histoire total, the dream to capture the entirety of the human past seems a little far-fetched to be more than a flashy catchphrase. Quantitatively speaking, historians may never capture the total, as history is never about the entirety of past-times but about selectively categorising the past into present inquiries. Hence, the ‘total’ has existed in the minds of historians than anywhere in the real world among many schools of historical thought. As the idea of ‘total history’ has changed over time to indicate different types of histories, total history is not defined by a particular spatial or temporal range or a specific scale of analysis; rather, it exists as a heuristic value according to what historians regard as the ‘total’ compared to their conventional frameworks of historical analysis.

What is Total History?

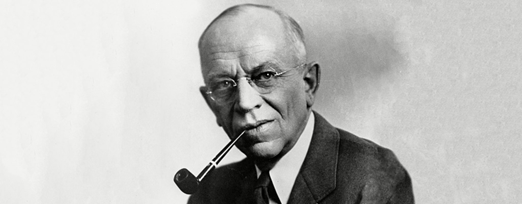

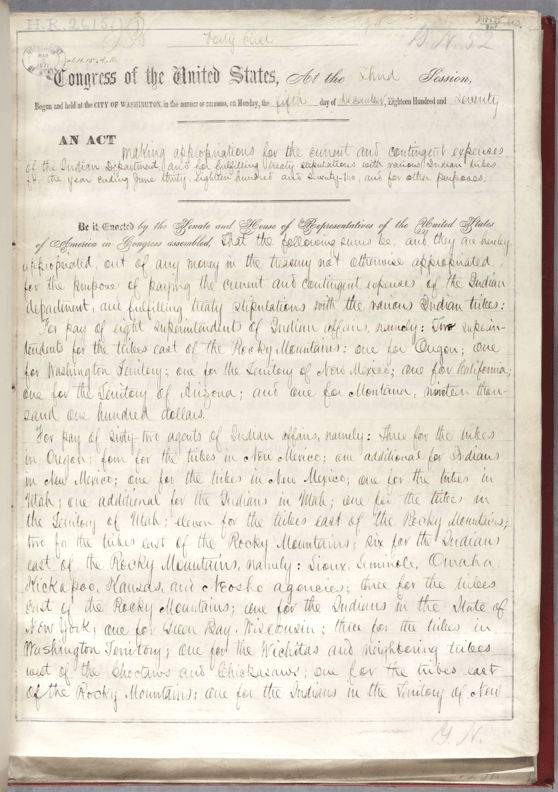

Total history’ has changed to encompass different meanings over time. Historians, as early as in the twelfth century (Bernard Itier, Chronicle), have generally assumed their works to account for the totality of their subject matter. However, ‘total history’ as an outspoken historical subdiscipline began with the Annales school of French historians in the early twentieth century. Early Annales historians like Fernand Braudel distinguished their practise of the ‘total external’ – the deep, slowly-changing geographic and economic structures – from the ‘event-based’ histories of the short-term political (Mediterranean, 1949). Other historians like March Bloch or later historians of the Italian microstoria school put forth the idea of ‘the total internal,’ arguing that the total only existed inside people’s minds and social relations. Recently, environmental historians have advocated for a total history of humankind as a geological agent, as the concept of the Anthropocene encouraged historians to consider nature as a historical protagonist. As such, the idea of ‘total history’ has constantly changed according to what historians have regarded as the ‘total’ as opposed to conventional frames of analysis used by their contemporaries. Hence, total history is a subdiscipline that aims to expand the frameworks in which historians conduct their analysis, rather than a term that denotes a particular type, scale, or spatial range of historical writing.

The term ‘total’ is often misunderstood. J.H. Elliott, in his review of Braudel’s Mediterranean, criticised that total history is ‘not dissimilar to total war’ as ‘in both instances, you throw in everything you’ve got,’ implying that the ‘total’ did not mean anything more than a mere aggregate of different types of histories without any distinctive features of its own (1973). Moreover, certain microhistorians, especially those who embraced the postmodern ‘incredulity toward master-narratives of all types’ (Jean- François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition, 1979), have critiqued the very notion of a ‘total’ history. Sigurdur Magnússon commented that by focusing on the uniqueness of the individual, microhistory denied the possibility of any overarching narratives (‘The Singularity of History’, 2003), while Giovanni Levi critiqued that the purpose of microhistory is to reduce the scale of analysis to undermine large-scale paradigms (‘Frail Frontiers?’, 2019).

However, these criticisms towards total history assume the ‘total’ is interchangeable with the ‘macro’ or the ‘global.’ Though colloquial uses of the word ‘total’ may have similar meanings to the macro (macroscopic analysis conducted on large groups of individuals) or the global (an extensive spatial range across geographic ranges), total history is not necessarily associated with large scales nor wide spatial ranges.

In terms of scale, the ‘total’ does not necessitate historians to focus on the macro. In The Cheese and the Worms (1976), Carlo Ginzburg wrote about the peasant culture during the Inquisition in sixteenth-century Italy from a microscopic scale of a single individual, a miller named Menocchio. From the fragments left by one idiosyncratic individual, Ginzburg constructed the totality of an unwritten peasant culture obscured from the view of previous historians.

Moreover, total history has also been written in small spatial spheres. Take, for example, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, who wrote the total history of a single village by examining the ecological, cultural, religious, and sexual relations of its occupants (Montaillou, village occitan, 1978). Though certain total histories do cover wide spatial or temporal ranges, total history itself is not related to a particular scale nor any temporal or spatial range. These criticisms misunderstand total history as a field that quintessentially aims to establish definitive meta-narratives across wide spatial frames or macroscopic scales: neither of which concerns the aim of total history.

The Total External

History does not aim to establish a definitive ‘totality’ of the past; rather, historians seek to expand the frameworks of historical analysis to one in which their contemporaries are not accustomed to operating. To understand what frameworks historians try to expand requires considering the historiographical context in which different types of ‘total histories’ were written. To historians of the ‘total external’ such as Braudel, the ‘total’ meant considering structural factors external to human relations – the geographical and economic structures that shaped human interactions in the Longue Durée.

For instance, in writing about the Battle of Lepanto in The Mediterranean, Braudel challenged the human-centricity of the Histoire événementielle (narrative-based history focused on historical events) practised before him. As he downplayed the importance of the event itself as ‘surface disturbances’ and ‘crests of foam’, Braudel emphasised the deep, underlying structures that preconditioned the battle before its occurence (1949). Moreover, in Out of Italy, Braudel opposed the historian Jacob Burckhardt in interpreting the Italian Renaissance (1974). While Burckhardt periodised the Renaissance as a two-hundred-year conjuncture characterised by unique individuals, Braudel sought to identify a deeper explanation of the Italian Renaissance as a continuity of long-term historical change. As such, the Braudelian ‘total history of the external’ sought to bring the historian’s attention to the deep, structural factors beyond the fleeting, ‘short-sighted’ human relations in political and diplomatic history.

The Total Internal

This ‘expansion of frameworks’ stands the same for another school of total history: the ‘total internal.’ Historians of the French Mentalités school focused on the collective ideas that escaped individuals to form the total. Jacques Le Goff characterised this mode of total history as studying ‘that which is common to Caesar and his most junior legionary… Christopher Columbus and any one of his sailors’, thus constructing the ‘total internal’ from the collective ideas between human relations (Mentalités, 1983).

This mode of total history gained prevalence, especially after the ‘Cultural Turn’ of the 1970s. In this period, historians began focusing on the microscopic scale of individuals and small grassroots groups in their research. Whereas cultural historians before this period, such as Burckhardt or Johan Huizinga, tended to focus on high cultures of the elite while assuming high culture ‘trickled down’ to people at the grassroots level of society, microhistorians like Carlo Ginzburg established how historians could construct the entirety of the social relations within a whole peasant culture by looking at the records left by a single individual (1976). To these historians, the total could only be observed by reducing the scale of analysis to single individuals who served as ‘keyholes through which to view the world in which individuals lived’ (Tonio Andrade, 2010). Thus, the ‘total internal’ expanded the boundaries in which historians operated by incorporating these people marginalised from the top-down narratives of history before the Cultural Turn.

Total History Today

Likewise, environmental historians today – though the word ‘total history’ itself has generally fallen out of usage – have reinvented the old ambition to write a total history of humankind for the twenty-first century. Although historians practising Braudel’s structural analysis of the geological and the economic and Ginzburg’s small-scale archival research – both of which have generally become the norm of historical research today – claimed to be writing ‘total’ histories of their own, historians have only recently recognised the role of nature as an active agent in historical change.

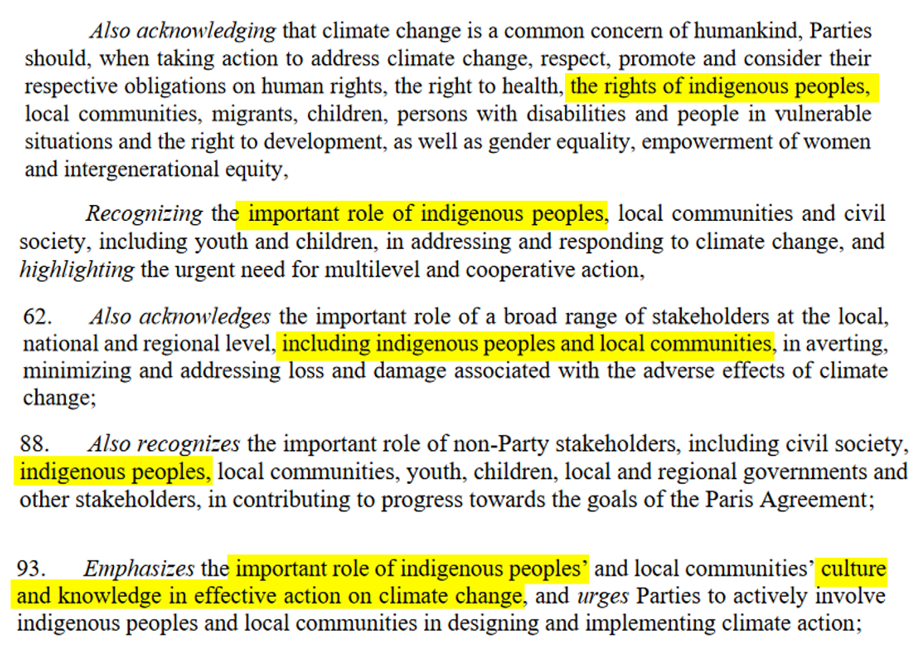

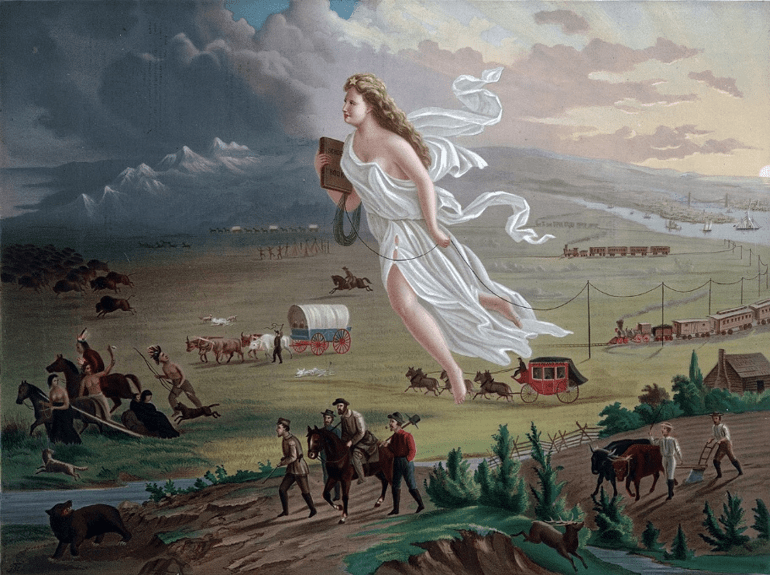

However, as the concept of the Anthropocene (the current geological age in which human activity has been the predominant influence on the environment) quickly arose along with the ongoing climate crisis (Nicola Davison, The Anthropocene epoch, 2019), historians have questioned whether the conventional boundaries in which they operated were too human-centred. In 1996, William Cronon revealed that historians tended to dichotomise the relation between human society and nature in a naïve way that underwrote human society as where the ‘significant’ acts occurred and portrayed the environment as a passive ‘untouched nature,’ underestimating the degree to which human activity affects the natural environment (‘The Trouble with Wilderness’). Thus, the rise of nature as a driver of historical change challenged the portrayal of nature as a passive, theatrical background on the historian’s canvas upon which humans were the sole actors.

Accordingly, ‘total’ historians of the environment have challenged our place as central ‘human’ agents of historical change. Works that focus on the history of germs, animals, or pathogens and their relations to humans have redefined the place of human agents in the historian’s canvas and have expanded the boundaries of historical analysis to non-human agents. In Can the mosquito speak?, Timothy Mitchell (2019) analysed how disease and malaria shaped warfare and economic change, undermining the idea that humans were in command of the environment as fully active agents. As Bruce Campbell emphasised in ‘Nature as historical protagonist’ (2010), it has only been since the enlightenment era that humans saw themselves as omnipotent agents against a passive, benign natural environment. Like Campbell, many ‘total historians’ today aim to expand the twenty-first-century historian’s scope of research to non-human actors and the environment by recognising the role of nature as a historical protagonist.

All of this is not to say history establishes a definitive ‘totality’ of the past. Every historian inadvertently prioritises some aspects of the past in choosing what better represents the ‘total.’ Historians of the ‘total external’ prioritise unchanging geographic and economic structures than short-term events, while historians of the ‘total internal’ disregard some parts of the past that are beyond the individual’s cognition in pursuit of a total history of the mental world. Nevertheless, the objective of total history has always been to achieve a comparative total by expanding the frameworks upon which historians operate. This is demonstrated by an active interest in interdisciplinary approaches shared by total historians of the ‘external’ and the ‘internal’ alike (Marc Bloch; Lucien Febvre, 1929). As total historians incorporate methods used in geography, economics, anthropology, or the natural sciences to the historian’s toolbox, they challenge the conventional frameworks in which historians view the past. Thus, the aim of total history is to expand the boundaries in which historians operate, not to claim their works to be definitive ‘totalities’ of the past.

In 1973, Le Roy Ladurie stated, ‘by the year 2000, historians will either be computer programmers or will no longer exist.’ In his remark, Le Roy Ladurie assumed historians had already expanded on all possible frameworks and that the only thing left of historical research would be the job of digital computers and quantitative analysis, which operate within the frameworks established at the time (‘L’historien et l’ordinateur’) Living in the twenty-first century, we know this has certainly not been the case. As conventional ideas of the ‘total’ are challenged, historians have been confronted by the elements to which they had been turning a blind eye: first to the ‘total external’ that revealed factors beyond the sphere of human relations and politics; then the ‘total internal’ which revealed the grassroots totality that had been marginalised by the top-down narratives before the Cultural Turn; lastly, the environmental total that redefined our position as human agents in relation to the environment and non-human agents around us. Thus, the historian’s work is only ‘total’ as they seek to expand the frameworks in which historical research is conducted.